Back in March and April 2020, you probably saw several variations of the following headline:

Will the COVID-19 pandemic result in a baby boom?

If you dug into the articles, though, you likely found that experts were somewhat in agreement. There wouldn't be a baby boom; in fact, we might see the opposite, and they had a number of reasons for believing that:

- It's a time of heightened stress and uncertainty.

- Disasters rarely lead to a significant increase in birth rates, despite the conventional wisdom.

- The U.S. birth rate had already been in decline for decades.

We're a year on from the start of the pandemic, and these theories have been confirmed. Not only are we not experiencing a baby boom, but we're in the middle of a baby bust.

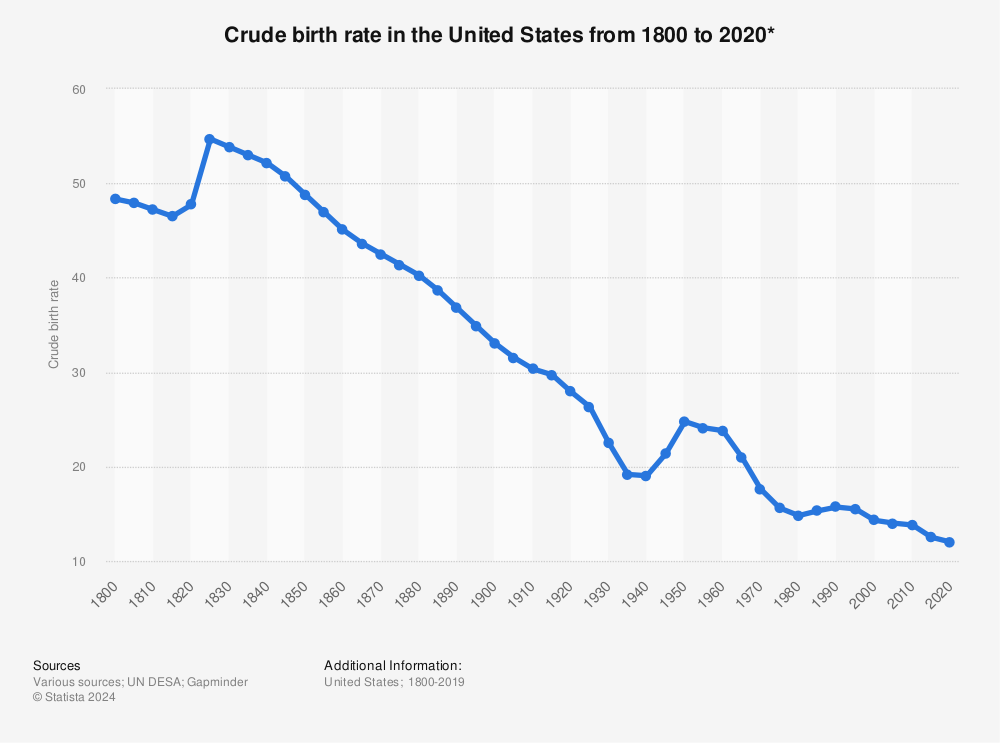

The pandemic likely exacerbated a trend that's been evident for decades. Since 1950, the birth rate in the U.S. has been on the decline. In fact, if you eliminate the baby boom that followed World War II, the birth rate has been in decline since the early 19th century.

In 2020, the crude birth rate in the U.S. was 12 live births per thousand people, and this number is expected to get marginally lower in the years to come. So, let's put aside the pandemic for the moment and ask:

Why is this happening?

- The first explanation, which derives from the 1960s and 1970s, is that women joined the workforce in greater numbers, with couples often delaying having children and ultimately having fewer than they used to.

- The continuing decline is also likely due to widening income inequality and the fact that millennials – the people we'd expect to be having children right now – are saddled with debt and can't afford it.

This isn't just an American problem, either. In Japan, economic insecurity has led to a deleterious drop in the birth rate. Experts there blame the growth of the nation's "irregular" workforce, the 40% of workers who piece together temporary gigs instead of having a stable job. That percentage in the U.S., which we'd probably refer to as "freelance" workers, has been creeping up as well.

The drop in births in 2021 is going to be more severe than in previous years due to the pandemic. The Brookings Institution estimates that 300,000 fewer babies will be born in 2021 than we would have expected without COVID-19. Birth rates are often tied to unemployment, so we'd expect births to remain low until unemployment returns to its pre-pandemic level (about 3.7% in 2019 – it was about 6.3% as of February 2021).

Ok, but why is it a big deal?

The major issue is that the U.S. has a large aging population due to the aforementioned post-WWII baby boom. More than one out of every six Americans is over 65 and that number is expected to reach one out of five by 2030. The ratio of caregivers per senior who needs care is shrinking and another 10,000 people are retiring every day. The millennials currently having fewer children will still outnumber the younger generation when they become seniors themselves.

There are also economic considerations.

- Fewer young people means fewer workers paying into Social Security for large generations of retirees.

- A generation which has notably already struggled through two major economic crises – millennials – might not be able to save as much money for retirement as previous generations.

- Businesses will suffer too. Research suggests that losses to productivity due to informal caregiving are anywhere from $17B-$33B annually. (These include things like absenteeism, replacing employees who leave to care for a parent, and shifts from full-time to part-time work.) Employees with caregiving responsibilities also cost their employers 8% more in health care costs than those who don't. And the number of employees with caregiving responsibilities is only going to increase.

- Declining birth rates are correlated with declining interest rates and suppressed growth.

The U.S. population continues to grow, albeit at a slower rate than in decades past. Some of the slowdown in fertility in the U.S. has been offset with . But, birth rates are declining worldwide, and immigration can't make up for that on a global scale.

Perhaps the market will shift to meet these needs. One industry may fade so the professional caregiver industry can flourish. Makers of baby formula seeing declining sales could pivot to vitamin drinks for seniors. Just a thought.

But, on an individual and even a policy level, this trend can only be observed and prepared for. As The Wall Street Journal put it last week, "a shrinking workforce caused by births two decades prior is easy to see coming and difficult to do much about."