America is a different place now than when you were born, and certainly far different from when your parents were born. Societal attitudes have notably shifted on a number of issues including women's rights, health care, and America's position in the world. Sometimes these changes happened gradually; other times, they came quickly, as in the early 2010s when same-sex marriage rapidly became more widely accepted, a move driven primarily by the Millennial generation. (more on this later)

Below we'll explore some other key issues where Americans' opinions have evolved and what may have been behind those changes. In some cases, there are identifiable landmarks in time that allow us to see public opinion shifting; in others, it's a slower evolution based on years of activism and changing sensibilities.

Spanking kids

Gallup's poll on this issue goes back to October 1954, with the following question: "Looking back to when you were a teenager yourself, what kinds of punishment seemed to work best on children your age who refused to behave?"

Granted, this question doesn't ask 1950s parents specifically what THEY did to discipline their children, but it does give a view of what most people at the time considered acceptable. Here are the results:

- Whipping: 40%

- Taking away privileges: 25%

- Being kept at home: 11%

- Given a "good talking to": 8%

- Made to sit in a corner, sent to their rooms: 3%

- Other: 12%

- No opinion: 8%

"Whipping," according to Gallup, incorporated a variety of physical punishments, including "'beating,' 'shellacking,' 'spanking,' [and] use of the 'strap' or 'stick.'" Additionally, 55% of adults in 1954 agreed that teachers or other school officials should be allowed to give children a "licking," should it be deemed appropriate.

That second part, corporal punishment in schools, was widely accepted for a long time and only came into question relatively recently. A number of states took measures to ban the practice following a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1977 that said corporal punishment in schools did not violate the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution. The District of Columbia and 23 states banned the practice between 1977 and 1994. Today, 16 states still either have no ban on corporal punishment or have only banned it for students with disabilities. That being said, it is not widely practiced anymore.

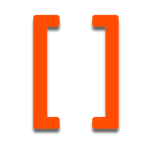

When it comes to spanking one's own kids, though, that's another story. Americans favor spanking kids less than they used to, though not by as much as you might think. In June 2016, a Gallup poll found that 62% of U.S. parents approve of spanking, down from 74% in 1946. This number is likely to decrease further in the coming decades, as a 2014 YouGov poll found that 43% of those 18-29-years-old approved of spanking, compared to 66% of those between 30-44, and 74% of those over 65. Of course, it's not definite that attitudes will change. Those young people who are against spanking might change their minds when they become parents themselves.

For what it's worth, new research suggests that spanking children hinders brain development and decision-making in similar ways to more serious forms of abuse.

Guns

As you might expect, public opinion on guns is part of an ongoing seesaw battle between Second Amendment activists and gun control activists.

Over the last 20 years or so, two things generally increase after mass shootings: support for stricter gun control laws and gun sales. The news cycle plays an important role in the ebb and flow of public opinion on this issue. Support for stricter laws is highest in the immediate aftermath of a tragedy, but that support somewhat recedes when mass shootings are out of the news.

A Quinnipiac poll taken just after the massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida in February 2018 found two-thirds of Americans wanted stricter gun laws. Only two months later, that number decreased to 56%. That's a staggering drop over such a short period of time.

In general, however, a majority of Americans do support enhanced restrictions on gun ownership, including universal background checks, a ban on assault-style weapons and high-capacity magazines, and a 30-day waiting period on gun sales, and they have for some time.

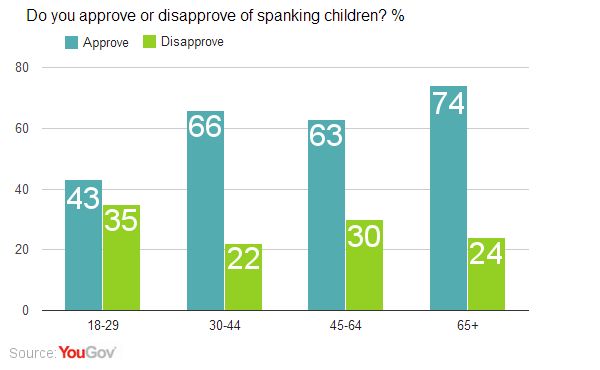

Since 1990, Gallup has only conducted a few polls where a majority of Americans didn't want stricter gun laws. Of course, as you can see in the graph above, support for enhanced gun restrictions has actually decreased overall in the last 30 years, likely owing to successful messaging efforts by the gun lobby. The election of President Obama in 2008 also helped gun manufacturers, as support for restrictions decreased and gun sales improved during his first term.

Public opinion may matter less in this issue than it would for something else. Despite a majority of Americans wanting several specific gun reforms, Congress remains hopelessly deadlocked, and sweeping change is unlikely. Robert Gebelhoff argued in The Washington Post in 2019 that the majority simply isn't passionate enough. At any given time, 55-70% of Americans may want stricter gun laws, but relatively few Americans ever list this as their top legislative priority. Since the issue always seems to fade into the background in the months following mass shootings, it'll keep being easy for Congress to ignore.

Race

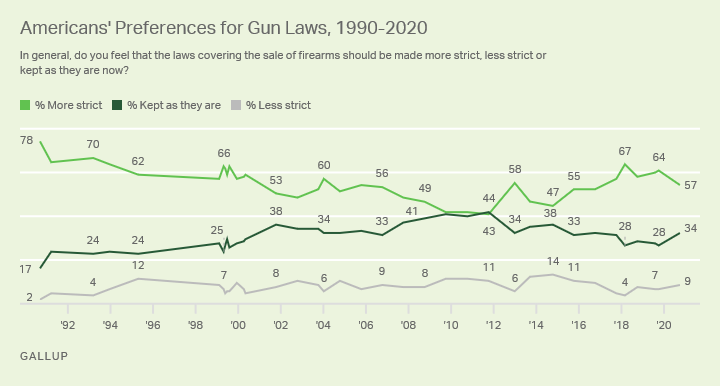

Race relations, police violence, and the Black Lives Matter movement also see rapid changes in public opinion depending on what's going on in the news. Take this astonishing statistic: A USA Today/Ipsos poll from June 2020 found that 60% of Americans described the death of George Floyd as murder; by March 2021, that number dropped to 36%. While a higher percentage of individuals in March 2021 classified former officer Derek Chauvin's actions as "negligent," poll respondents were also more likely to say "it was an accident," "the police officer did nothing wrong," or that they didn't know.

That's just a poll about one specific incident, but it's reflective of how malleable Americans' views on race are, even in the short term, and how much the respondent's race matters. (64% of Black Americans in March 2021 described what happened to George Floyd as "murder" compared to 28% of white Americans.)

Here's another example:

Support for and opposition to the Black Lives Matter movement surged in the months after George Floyd was killed. Again, much of this likely had to do with the news coverage people were watching, which largely conformed to what their viewers already believed. Those who watched MSNBC saw the George Floyd/Derek Chauvin footage and police firing tear gas into crowds; and those who watched Fox News saw vandalism and property on fire across the U.S. Our current media landscape has a way of reinforcing and strengthening biases, leading to odd graphics like the one above.

One major thing to note is that a higher proportion of Americans appeared to have made up their minds since summer 2020. At the beginning of that year, about 25% of registered voters said they neither supported nor opposed the Black Lives Matter movement. By October, that figure was down to 12%, and has held steady ever since.

But, let's go back in time a little bit on this to see how we may have progressed since one of the more tumultuous times for race relations in the U.S.: the 1960s.

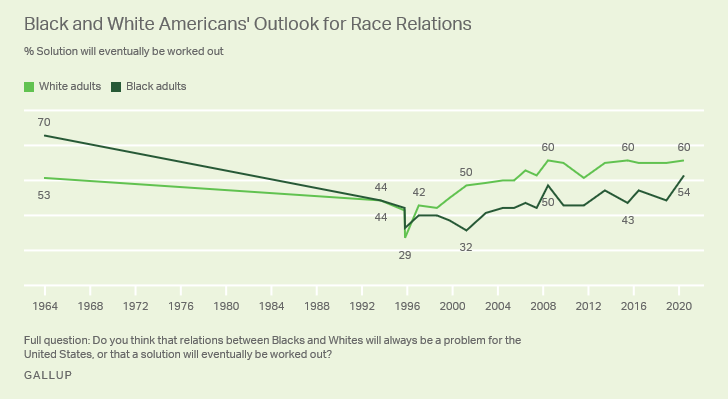

In December 1963, NORC asked both Black and white people the following question: "Do you think that relations between blacks and whites will always be a problem for the United States, or that a solution will eventually be worked out." 70% of Black people at the time said that a solution would eventually be worked out. That number dropped to 44% in the 1990s when Gallup started asking the question. It's recovered a bit since dipping as low as 32% in the early 2000s, but has never reached the high water mark achieved during the time of the civil rights movement.

White people have become significantly more hopeful in that respect over the last 25 years. 60% of white people now say a solution to race relations will eventually be worked out, a number which has held pretty steady since Obama was elected in 2008. The social activism of 2020 appears to have boosted that perception among Black adults as well – 54% is the highest that number has been since Gallup started asking the question again in the early 1990s.

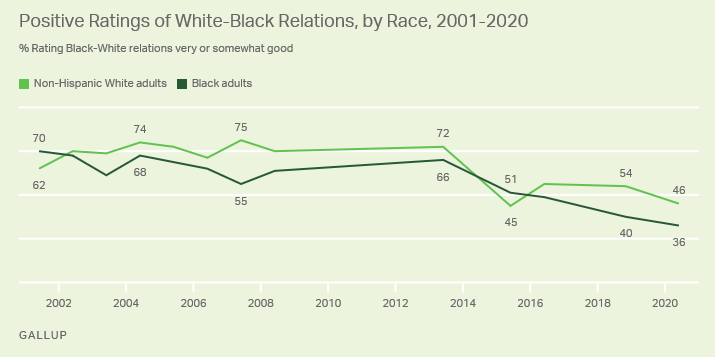

Nevertheless, the percentage of people who say Black-White relations in the U.S. are "very good" or "somewhat good" is at a low point, particularly among Black adults.

Here's one more poll for this section. In 1963, a Gallup poll asked white adults if they would move out of their neighborhood if many Black families moved in. 78% said yes. That question is not asked today, but if it was, Gallup would find it pretty difficult to glean much information from the responses. The percentage who answer "yes" would undoubtedly be far lower, but who would admit to such a thing in 2021?

This last question highlights one of the major problems in polling about race over time. The Overton window has shifted enough that Gallup would be criticized for even asking the question in today, and the percentage of white people who likely would move out of their neighborhoods if they became more racially diverse would be far less likely to admit it.

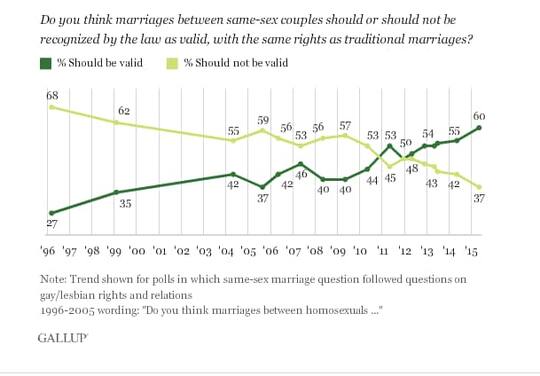

However, polling over time can also highlight when that Overton window has shifted. For example, same-sex marriage was firmly outside the window and consistently polled under 50% support...until it suddenly didn't anymore and became the law of the land. As recently as 1996, only 27% of Americans said same-sex couples should be allowed to marry, and 68% said they shouldn't. Progress on the issue was steady, and then sudden.

There are a few different theories as to exactly why this happened, and it's likely a mix of messaging, visibility, and the fact that a greater share of heterosexual Americans than in the past personally knew someone who was openly gay.

That 27-68 split in 1996 isn't all that far off from the 18-58 split in support for defunding police departments. It's a highly unpopular position now, but things can change quickly. In fact, when pollsters don't use the language "defund the police," and instead ask about specific policies, such as redirecting some police funding for mental health agencies to respond to emergencies, support skyrockets.

Just imagine what percentage of respondents would have supported that in 1963.

Share this article on Twitter.

Header image: Logan Weaver on Unsplash

About the writer: Jonathan Harris is a writer for Inside.com. Previously, he wrote for The Huffington Post, TakePart.com, and the YouTube channel What’s Trending.